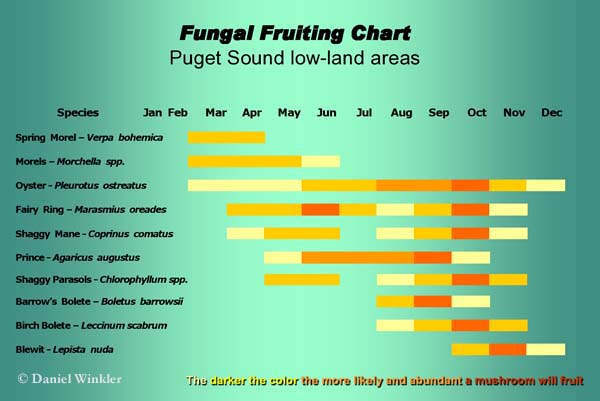

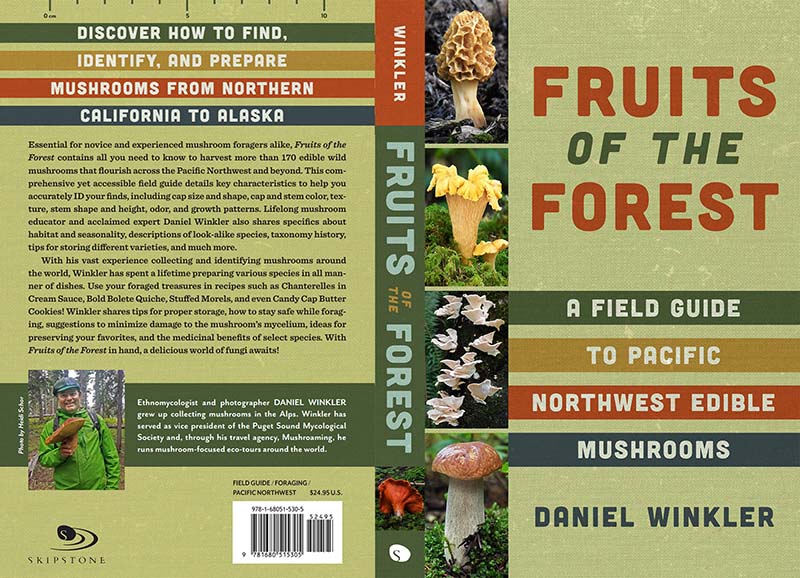

My Favorite Edible Mushrooms in the Pacific Northwest Information provided, i.e. for habitat and seasonality apply to the Pacific Northwest from a Seattle perspective. [Please do not solely rely on my descriptions and my photos for identification. In case you are not familiar with a mushroom, ask somebody who has survived his or her fungal forays and is familiar with the species you are intending to consume.] A virtual misidentification can have real consequences.... My new book: "Fruits of the Forest - A Field Guide to Pacific Northwest Edible Mushrooms"My "Field Guide to Edible Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest" Buy here Go to:

Shaggy Parasols - Chlorophyllum rhacodes, C. brunneum & C. olivieri. In the Pacific Northwest grow three tall, edible Chlorophyllum species: Ch. rhacodes, Ch. brunneum and Ch. olivieri. In the past these three were all identified as Macrolepiota and clustered under M. rhacodes. However, DNA analyses has shown (Vellinga 2002/2003) that these fungi are more closely related to Ch. molybdites than to Macrolepiota procera, the Parasol. Some people have very unpleasant allergic reactions to eating these superb mushroom. That's why it is not available in trade. Best is to start out with a few bites to see how your organism relates to the ingestion of this organism, and if everything is fine to really enjoy the shaggy parasols the next day. [a key to differentiate these three similar shaggy parasols can be found at http://www.svims.ca/council/Chloro.htm] | ||||

Chlorophyllum olivieri (Barla) Vellinga Gray Shaggy Parasol | ||||

Most striking of this big, beautiful and very tasty mushroom is the scaly cap, which it is named. Shaggy Parasol move through a "drumstick" phase, before the mushroom opens to an umbrella, hence "parasol", the French name coined for its big and more famous cousin Lepiota procera, which is not widely distributed in the PNW yet. Drumsticks can be turned magically into umbrellas by inserting the stipe in a water-filled glass of after collection. Umbrellas are easier to fry. You can find the Shaggy Parasol in spring and fall in nearly all forested parks and many back yards in the suburban PNW. This patch is in my yard under a Douglas fir, another one under a true cedar. I hold the Shaggy Parasol as the PNW most abundant and tasty backyard mushroom. Chlorophyllum brunneum Vellinga Brown Shaggy Parasol  A spring fruiting of the Brown Shaggy Parasol - Chlorophyllum brunneum in St. Edwards Park, Bothel WA. Photo: April 22, 2006 |  Fall fruiting of Gray Shaggy Parasols - Chlorophyllum olivieri (=Macrolepiota / Lepiota olivieri) in my back yard under a Douglas fir, Kirkland WA. Photo: 9-9-2008 There are three tall [15-25 cm / 6-10 in], edible Chlorophyllum species, such as Ch. rachodes, Ch. brunneum and Ch. olivieri. In the past these three were all identified as Macrolepiota and clustered under M. rachodes. However, DNA analyses has shown (Vellinga 2002/2003) that these fungi are more closely related to Chlorophyllum molybdites than to Macrolepiota procera. Chlorophyllum molybdites [growing in Hawaii] is a very similar, tall, light-green spored species that causes extremely unpleasant, but at least non-lethal poisonings in climates with hot summers or in the tropics or subtropics. So far the Green-spored Shaggy parasol has not been reported in the PNW, but be very careful collecting shaggy parasols in warmer areas. UPDATE: Due to climate change Ch. molybdites aka the Vomiter has now be found in the PNW at least in three sites: S-Willamette Valley OR, Walla Walla SE-WA and in Everett WA! Also, be aware that there are similar looking small [height and cap diameter below 10 cm / 4 in.], Lepiotas, some of them even deadly. If you have identified this mushroom positively and you know that you will not react adversely as a few people do, you can enjoy a nice meal. Like most mushrooms, they need to be cooked thoroughly before consumption. I love to fry them gills down in butter until they turn light brown, flip them shortly and then put them on a toast with herb butter and a thin slice of parmiggiano. They can be used in many other preparations, they have a strong, gamy taste, very umami [=savory]. They can stand up to a generous amount of garlic. In Slovenia I learned to use them as a pizza base, yummy! | |||

CustomWritings - professional essay services for students who need help with writing about mushrooms. Chlorophyllum rhacodes (Vittad.) Vellinga White Shaggy Parasol  Note the light whitish cap color, which sets Chlorophyllum rhacodes [formerly Macrolepiota rachodes (Vittad.) ] apart from Chlorophyllum olivieri. The bulbous stem base that is not abrupt as in Ch. brunneum. These specimens were encountered in a park lawn in Bothel WA. Nov 2, 2010. Note the scientific species epithet / name was recently changed from rachodes to now rhacodes, the way it might seem correct if Greek. However, the author of the name Vittadini did not refer to a Greek word, but an Italian name of a disease that produces scaly skin. The "correction" of the name is quite infuriating to the people who looked a bit deeper and did not just use a Greek dictionary. Write my paper for me request? MyPaperDone.com cares about students and will provide quality writing help. | ||||

Agaricus augustus Fries The Prince | ||||

Lilith introducing a charming young Prince to her father. Everybody loves his rich aroma of marzipan [=almond]. Kirkland WA, June 20, 2008 © Daniel Winkler |  That's how suburban Princes present themselves in their prime. Full 25 cm (10 in) across! Not a single worm! The still pinkish gills, which soon will turn dark brown just were exposed. The skirt-like partial veils clearly visible. Also very typical is the scaly, reddish brown cap Redmond WA, October 5, 2008 © Daniel Winkler | |||

The Prince is definitely one of the best edible mushrooms. The almond aroma is just awesome and it makes it easy to identify this Agaricus, supposing one knows how to recognize the genus. Many other Agaricus species are really hard to identify to species level. For years I searched without success for the prince, since I was clueless about its fruiting season. I looked for the prince during the fungal fall flush. However, the prince likes it warm and needs a bit of rain. So, in western Washington it fruits usually between May and September, in mild years into October. Most patches fruit twice a year, in late spring or early summer before the typical summer draught and late summer or early fall, before it gets too cold. I never found it out in the woods, only in man-made environments. It is actually quite abundant in suburbia, but you have to beat the worms to it. So once I find one I check my other patches. Often it grows in sterile landscaped areas, like barked beds and areas under conifers, preferably in apartment building complexes. Most of my dozen or so patches in Kirkland I have spotted driving by - "I break for mushrooms". Its big size, caps can reach 12 in (30 cm) across, really helps for "remote detection".  A basket full of princes, Kirkland WA, September 2004 © Daniel Winkler On the left, Agaricus moelleri, the Flat-topped Agaric, formerly known as A. praeclarisquamosus. Not only is the old name a mouthful, but you do not want to put this Prince impostor in your mouth, since Agaricus moelleri is regarded as poisonous. They are not badly poisonous, might even be used medically as a laxative or purgative. I am just joking here, there is no medical research for this application, but they had me glued to the loo for 30 minutes. Arora wrote that a few people seem to be able to eat this mushroom without problems, and I learned I liked the taste, but did not like the consequences. It should have a bit of a phenolic / chemical smell when scratching the stipe base, which should also be detectable when cooking it, but does not have to have that unpleasant odor. This is the most abundant Agaricus in the Seattle area. Often it fruits later than the Prince, but sometimes also side by side. However, the Prince (Agaricus augustus) is almond scented and has a more reddish look than the cold, grayish tone of Agaricus moelleri. Short description: Large, fleshy mushroom; cap covered by minute blackish-brown scales. Free, close gills, young pallid to pinkish turning chocolate brown. Whitish stem with big ring, stem base when cut staining yellow, odor mild or phenolic, taste mild to metallic or phenolic, | I like to eat the prince raw in a salad or just with a bit of balsamico and parmiggiano, very tasty. But frying them up works just fine too. When the gills get too dark in mature specimen, the dish will look better when the gills are being scratched off with a knife blade before frying [Gills from all Agaricus species typically turn from pale white and light pink to dark brown with the maturing of the spores.] After all this praise comes the bummer. Agaricus-species are specialists in concentrating heavy metals, such as lead and cadmium, a well known capacity in myco-remediation [mushrooms used to clean up toxic sites by concentrating toxic pollutants]. Now, suburban princes can easily have their share of lead, especially collected along a road. Remember the days when lead was used in gas. Research from the 1970s in Germany showed that mushrooms on regular soils can reach cadmium concentrations a multiple of cadmium polluted sea food. A recommendation from the German Mycological Society (see the DGfM advisory) suggest to limit consumption of wild mushrooms to a half a pound per week. However, recently I came across a reference that suggested heavy metals in fungi are not really soluble and thus toxicity would not be this great an issue. Got to find the science behind that assuring statement. If anyone has any references, please let me know.  Looking under the "kilt" of the Prince. The partial veil is about to rip. Once separated from the edge of the cap it hangs skirt-like down from the stipe. Also, note the pink gills and the scaly stem; all important characteristics of the prince. Kirkland WA, October 5, 2008 © Daniel Winkler "Prince Imposter" - Agaricus moelleri - Not edible  Agaricus moelleri, a.k.a. A. praeclarisquamosus, the Flat-topped Agaric, an inedible species common in suburban areas on the West coast. Kirkland WA, October 5, 2008 © Daniel Winkler | |||

Lepista nuda ( (Bull.: Fr.) Cooke | |

A Blewit found in Tibet The Blewit is a saprotrophic fungus, feeding of decaying biomass, thus its sites are quite unpredictable. The sites I have collected from are often good for a year or two, maybe three years and then the biomass might be exhausted. But next fall other Blewit hordes will pop up in a range of unsuspected places, like in meadows and mixed forests and in parks and yards. Being a saprotrophic mushroom, cultivation has succeeded and some high-end stores are selling Blewits. However, since they are still imported from Europe one has to spend $20 to $30 a pound and that seems over-prized to me.

| The Blewit (Lepista nuda or also Clitocybe nuda) is one of the latest fruiting good edible mushrooms here in the Pacific Northwest. It appears from fall into early winter, mild frosts seem to rather stimulate its fruiting than to terminate it. For beginners this mid sized mushroom is not so easy to identify. First step is looking for purplish mushrooms and there a more than one would expect, especially Cortinarius has a range of bluish mushrooms, some like C. alboviolaceus are very similar, but have among other subtleties brown spores . And sometimes the purple of this mushroom with a smooth cap and in-rolled margin when young can be in the red spectrum, sometimes more bluish and sometimes more dull and brownish. Thus the color alone is not that reliable. For me personally the fruity odor that comes closest to the smell frozen orange juice concentrate was a very important character for feeling safe with the ID. But better check also for the stout, veil-free stem with purple mycelium threads on the base. The spores are pinkish.  Very bluish Blewit growing in the duff of a Pacific Red Cedar in Kirkland WA, Nov. 16, 2009 |

Marasmius oreades (Bolton: Fr.) Fr. Fairy Ring mushroom | |

Marasmius oreades, the fairy ring mushroom is distributed in lawns all over the northern hemisphere (North America & Eurasia) and introduced to New Zealand. It is a choice edible. It is not the easiest mushroom to identify in the beginning being, since it is one of the informal and infamous group known as LBMs, little brown mushrooms. Marasmius oreades is light brown, the umbonate central disc of the cap is a bit darker brown when young, and turning paler when aging. The edge of the cap tends to be undulate when the cap expands. The photo above shows the change through the different development stages nicely. It is white spored and its gills are fairly well-spaced and broad while being white to pale tan. A very helpful ID tool is its pliable stem. When I am unsure if it is a fairy ring mushroom, I first check the stem pliability. If it breaks easily, there is no point in pursuing further identification. Also helpful is the fact that the fairy ring mushroom is limited to lawn habitats and that it reoccurs on the same site year after year. Just make sure that the lawns have plant diversity including weeds and moss. A lawn without weeds often indicates application of chemicals, which very well might be concentrated in the mushroom and you better don't eat them. Some people manage to confuse this mushroom with the "Sweater", Clitocybe dealbata, which is a poisonous muscarine-containing mushroom that will give you amongst other symptoms nasty sweats. Usually the Sweater is white, funnel-shaped and has fully decurrent gills. © Photo Daniel Winkler, June 3, 2006, Kirkland WA |  A small basketful of fairy ring mushrooms. Marasmius oreades pops up in my lawn several times a year. It fruits as early as April, again during summer, if there is enough water and as late as November. The grass where my Marasmius grow is the only lawn in my yard that I water. The lawn is clearly disturbed where the mycelium grows, but the mushrooms taste much better than the grass. Although it is a bit tedious to pick, since it is quite small and usually plentiful, it is absolutely worth it. I always have to go on my knees armed with scissors before lawn mowing. It is has a rich nutty taste and dries easily and is reconstituted quickly. If I only pick a few mushrooms I dry them and add them to the jar full of dried Marasmius. They are perfect to add into sauces without needing long reconstitution time. This could be explained with the unusual capacity of Marasmius to fully revive when there is moisture available again after having dried out completely. Also, I love to caramelize them by frying them in butter and sugar and then using these fairy caramel caps by sprinkling them on salads. © Photo Daniel Winkler, June 3, 2006, Kirkland WA |

Coprinus comatus (O.F. Muell.: Fr.) Pers Shaggy Mane

Sparassis radicata Weir The Western Cauliflower Mushroom | |||||||||||||||||||

Breitenbush Hot Springs, Oregon 10-23-2010 © Daniel Winkler Sparassis radicata grows near the base of a host conifer tree, often Douglas firs. It is connected to the root system by a single underground stalk. There are not too many individuals out in the woods, but when one is lucky enough to find one, that will be good for several meals. The cauliflower mushrooms fruits in the same location for many years with one individual in late fall. Joe Ammirati suggests to leave the base when collecting for food, so that it will fruit the next year. They are easy to spot once you find the host tree again. However, I seem not often to find the host trees again or rather get beaten to it by someone else. The western Cauliflower mushroom is often listed as Sparassis crispa (Wulfen) Fr. Although Sp. radicata was described by Weir in 1976 for growing on PNW Douglas fir, consecutive mating and culture test challenged the erection of a new species different from the Cauliflower mushroom distributed on the East Coast and in Europe. Thus Sparassis crispa remained in use, however more recent phylogenetic studies confirm that the Western Cauliflower mushroom is distinct from Sparassis crispa (Wang et al. 2004). |  Bridal Trails State Park, Bellevue WA - Oct. 4, 2005 © Daniel Winkler Sparassis radicata, the Western cauliflower mushroom, is one of the easiest mushrooms to identify (not that this would mean that people who don't bother to really check, would not manage to confuse this mushroom with a coral fungus or a pile of egg noodles). Source: Wang Z, Binder M, Dai YC, Hibbet DS 2004. Phylogenetic relationships of Sparassis inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial ribosomal DNA and RNA polymerase sequences. Mycologia, 96(5), 2004, pp. 1015–1029. | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Boletus rex-veris Arora & Simonini Spring King Bolete | |||||||||||||||||||

The Spring King (Boletus rex-veris) resembles the King bolete (Boletus edulis) quite a bit. It is also a big bolete with a smooth cap, which is light brown to reddish brown. When young the cap has a white "dusting", known as bloom. The tubes are small and white, turning yellowish and green with age. The stem is massive, wider at its base, cream-colored when young and turning brownish with age. It has a whitish network on its surface, known as reticulation, typical for most members of the Boletus genus. It has a mild, nutty taste, very firm flesh and is a choice edible mushroom! It can grow in clusters, something Boletus edulis shows extremely rarely. It does not stain blue, but the cap flesh might have a reddish tinge. As the name indicates it fruits in spring in mountain conifer forests of the Cascades and California's Sierra, usually feeding of snow melt and when lucky of spring rains, which can extend its fruiting season nicely. © Daniel Winkler, May 19, 2012. Eastern Yakima County, WA |  © Daniel Winkler, Western Chelan County, June 28, 2011., WA

| ||||||||||||||||||

In the Western lowlands we find the White king, Boletus barrowsii under introduced deciduous trees such as oaks (Quercus spp.), elms (Ulmus spp.). hornbeams (Carpinus spp.) and linden (Tilia spp.). Normally B. barrowsii is most common in the southwestern region of the US, where it is associated with pine, fir, spruce and live oak. In Eastern Washington it grows in conifer mountain forests but is rather rare. In the Seattle are it fruits through summer and in fall, whenever there is enough rain, but irrigation systems sometimes free this mushrooms from the uncertainties of weather. Here the enemy are reckless lawn mowers! Steve Trudell & Joe Ammirati (after Gibson's Matchmaker) state, "Generally considered to occur only in the Southwest. In Seattle, a very similar mushroom is fairly common in late spring under oaks and species of Tilia, such as lindens and basswood. Although it was felt that this had to be a different species, DNA analysis suggests it is B. barrowsii." |  Boletus barrowsii has a whitish to grayish cap with suede-like texture. Its pores are white when young, do not bruise blue and turn light brown-yellowish when old. The stem [with a reticulated upper part] ranges from whitish to grayish and can be darker than the cap. It is a choice edible mushroom, and I prefer its firm and aromatic flesh to our endemic mountain Boletus edulis, which is one of my absolute favorites. Both pictures: © Daniel Winkler, September 2010, Seattle area, WA | ||||||||||||||||||

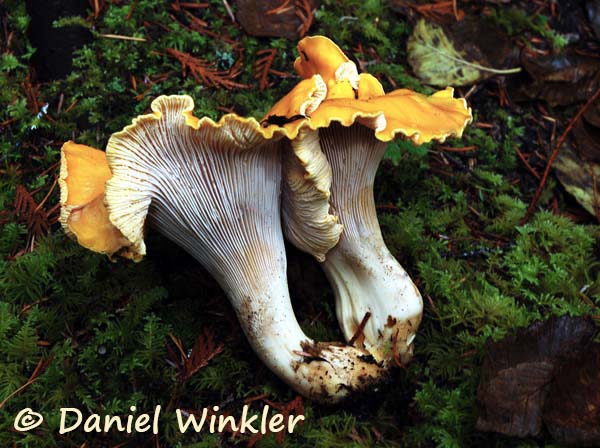

Cantharellus formosus Corner Pacific Golden Chanterelle | |||||||||||||||||||

A patch of freshly popped still small Golden chanterelles (Cantharellus formosus) encountered in the Cascade foothills East of Seattle. It can take Chanterelles weeks to grow to full size like the specimen on the right. Chanterelles can grow and persist for a very long time. The Oregon Chanterelle study observed one Pacific Chanterelle living for nearly two months! 9-13-2013 © Daniel Winkler  What a haul! Collecting all these chanterelles was the easy part. It only took 3 hours. However, cleaning all these chanties and cooking them in order to freeze them kept us busy on many evenings the following two weeks. We really learned we do not need to pick all the chanterelles we can gather, only because they are out there. It is fine to leave many behind. |  A giant specimen of Cantharellus formosus on the side of a small chanterelle. Compare the size of this chanterelle to the hemlock and Doug fir needles or the leaves of Salal (Gaultheria shallon). The Golden chanterelle is the most abundant of all coastal chanterelles in the Pacific Northwest. There is no other places on this globe that offers a comparable chanterelles bounty as does the Pacific Northwest. This is Chanterelle heaven, no doubt! Eastern King County, WA, Oct. 24, 2007 © Daniel Winkler  My daughter Lilith is showing some good-sized chanterelles. The chanty in her left displays that strange frizzed look some chanties fall for. Oct. 2004 © Daniel Winkler | ||||||||||||||||||

Cantharellus cascadensis Dunham, O'Dell & R. Molina Cascade Chanterelle | |||||||||||||||||||

Both Photos: Breitenbush Hot Springs 10-23-2010 © Daniel Winkler |  Cantharellus cascadensis is one of the three big PNW chanterelles. It grows in a similar habitat as C. formosus, the Pacific chanterelle. In shape it is closer to C. subalbidus, the White chanterelle, but its cap color is closer to the Pacific chanterelle. However, the cap of the Cascade chanterelle is often brighter yellow than the cap of the Pacific chanterelle and its stipe is club-shaped or widens at the base, where as the stem of the Pacific chanterelle usually is narrowing or at least equal at the base. Another important and quite reliable characteristic is the thin margin of C. cascadensis. Thom O'Dell told me that before C. cascadensis was differentiated from C. formosus based on molecular analyses in 2003, commercial pickers already had their own name for this chanterelle, "the hybrid". In regard of taste it seems to me equal to the Pacific Chanterelle. | ||||||||||||||||||

Cantharellus subalbidus A.H. Sm. & Morse 1947 White Chanterelle | |||||||||||||||||||

Photos: Breitenbush Hot Springs 10-24-2008 © Daniel Winkler |  | ||||||||||||||||||

Cantharellus subalbidus, the White Chanterelle is endemic to the PNW. It is much paler than all the other chanterelles here. However, the whitish flesh stains yellow from handling and also in old age. Often it has a much thicker stem and is more stout than the two big yellowish-caped chanterelles, C. formosus and C. cascadensis. Often white chanterelles do not reach above the duff layer and are much harder to spot than other chanterelles. Personally I prefer its taste to C. formosus, but that could be a result of finding much less Cantharellus subalbidus than C. formosus. Cascade and White Chanterelles  Cantharellus cascadensis (left) and Cantharellus subalbidus (right) in a crate ready to be sliced for cooking. The Breitenbush Mushroom Conference always has a great mushroom cooking and tasting workshop offered by chef Michael Blackwell. Breitenbush Hot Springs 10-23-2010 © Daniel Winkler | |||||||||||||||||||

A Gathering of the PNW Chanterelles at Breitenbush Hot Springs Cantharellus subalbidus Cantharellus cibarius var. roseocanus  A picture from the ID table at the 2008 mushroom conference at Breitenbush Hot Springs, near Detroit, Oregon. The Pacific Golden Chanterelle Cantharellus formosus (lower left next to the purple pig's ear - Gomphus clavatus ), Cantharellus cascadensis (folds of the hymenium, the spore producing surface, are much lighter, rather whitish in fresher specimen and the cap bright yellow, See above a fresher sample), Cantharellus cibarius var. roseocanus - the rainbow chanterelle (top center right), sporting the deepest yellow folds and Cantharellus subalbidus, the white chanterelle. On the lower left Craterellus tubaeformis aka yellow foot. There was also a blue chanterelle Polyozellus multiplex found in Breitenbush (see below). Judy Rogers and Susan Libonati were in charge of the ID table. Judy talked on Sunday about the PNW chanterelle diversity and I hope I did not misrepresent any of her statements here. Please note that all these specimen had been handled by many people and thus color changes are possible. 10-26-2008 © Daniel Winkler | |||||||||||||||||||

|  © Daniel Winkler, Salt Point State Park, Sonoma County CA, Jan. 19, 2008 The small size of this good edible mushroom is usually compensated by the fact that winter chanterelles occur in big numbers. However, one needs patience harvesting yellow feet. Jürgen from Mission BC introduced me to the use of scissors when collecting winter chanterelles. | ||||||||||||||||||

Polyozellus multiplex (Underw.) Murrill The Blue Chanterelle

| |||||||||||||||||||

Verpa bohemica (Krombh.) J. Schroet. Early Morel or Early False Morel [synon. Ptychoverpa bohemica (Krombh.) Boud]  © Daniel Winkler, Kirkland WA, April 19, 2008 | |||||||||||||||||||

I have been eating Verpas since many years and always enjoyed them without any ill effects. Please note some people get unpleasant reactions, such as gastro-intestinal upset or muscular dis-coordination after eating Verpa bohemica.Thorough cooking is absolutely necessary, some people parboil them before consuming. Overindulging seems to be a bad idea.  © Daniel Winkler, Kirkland, King County WA, April 19, 2008  A nest of Verpas on the base of a black cotton wood in Redmond Watershed Park. © Daniel Winkler, Redmond, King County WA, April 23, 2008 |  In the Pacific Northwest Verpa bohemica often grows in symbioses with Black cottonwoods (Populus trichocarpa or P. balsamifera subsp. trichocarpa). It is easy to time the fruiting of Verpas since it coincides with the flowering of North America's biggest deciduous tree, the Black cottonwood. Its flowering is widely advertised by its sweet smell. Below the stem of the left, leaning Verpa are fallen catkins and bud leaves, which are covered by an aromatic and sticky gum, which had many traditional uses by native people.  Spring morels (Verpa bohemica) are easily distinguished from true morels (Morchella spp.). The cap of spring morels hangs completely free of the stem. It is only attached at the top, hence another common name "thimble morel". The stem of true morels is completely fused with the cap; the whole mushroom is hollow. Also the stem of spring morels has a cottony stuffing, which is absent in morels.  A Puget Sound garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis pickeringii) sun bathing on an otherwise cool spring day (thanks Bonnie for identifying this Garter snake). However I wastold that it should be Thamnophis ordinoides, the NW Gartersnake based on head scale count. © Daniel Winkler, Redmond, King County WA, April 23, 2008 | ||||||||||||||||||

Morchella importuna M. Kuo, O'Donnell & T.J. Volk Landscape Black Morel

Sources: Gibson, Ian & Eli; Kendrick, Bryce 2008. MatchMaker- Gilled Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest 1.31 - awesome software, free to download! McKenny, M.; Stuntz, D.E.; Ammirati, J.F. 1987. The new savory wild mushroom. Western Producer Prairie Books, Saskatoon. 250 pp. Trudell, Steve & Joe Ammirati 2009. Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest, Timber Press Field Guide, Portland, 349 p. Winkler, Daniel 2011. Field Guide to Edible Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest, Harbour Publishing, Madeira Park BC, Canada, Fold-out, 16p.  Daniel's Fungal Feastability Function  This curve, incoincidently reminiscent of a mushroom cap, illustrates the distribution of edible (green) and poisonous (red) mushrooms within the large mass of mushrooms. Note, how few mushrooms are to be found in both extremes, choice edible as symbolized by a prime king bolete (Boletus edulis) and deadly poisonous ones, symbolized by Amanita phalloides, the Death cap. The majority of mushrooms out there falls in the gray middle, may be not toxic, but of questionable taste and / or consistency, too small or too slimy to matter or simply unknown. Now to make things even more mushy, this function falls differently for every mycophagist. For some poor mushroom lovers even the king bolete or a chanterelle lands in the red zone, however there is no known person indulging repeatedly in death cap feasts, but of course slugs and deer nibble it without ill effects. If you like my webpages, ordering my book on PNW Edible Mushrooms or my newly revised field guide is a nice way to support my work.  My New Book : Order Now Fruits of the Forest - Field Guide to PNW Edible Mushrooms, 170 edible mushrooms, 400 pages, 50 p. recipes  If you like my webpages, ordering my newly revised field guide is a nice way to support my work.

Last change: 6-15-2025 | |||||||||||||||||||